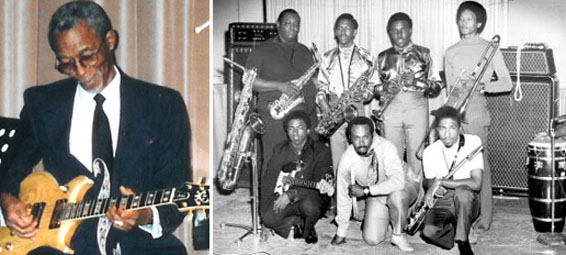

After researching for months and then working on the artwork for more months, I am finally relieved that the work is done and off to the fabricators. Since the Nasher Sculpture Center is planning a kick-off event for this commissioned site specific installation, I won’t steal their thunder by describing the work. In fact, what I want to write about in this post has little to do with the finished work and more to do with the impetus behind the creation of the work. I have for over 35 years spent my creative energies reclaiming African American history in installations that both invoke memory and emotion. I have researched my community’s past hurts and slights, its horrors and abominations, its beauty marks and its warts, all with the purpose of making my audience face history without apology. This latest project will help Dallas, particularly Black Dallas, face the truth about one aspect of Bishop College’s history, and hopefully place Bishop at the center of Black cultural development, a place it has rightfully earned. So often when things don’t play out the way we want them to, we tend to file away the experience in the “dead zone” file, hoping not to have to revisit the disappointing episodes of our failure. We either dismiss the experience or we reinvent it as something it never was. Such is the case with Bishop College. When I arrived in Dallas in 1980, I knew nothing of this little private HBCU nestled deep in South Oak Cliff. Bishop was on its last leg back then, limping along and trying to just hang on until some miraculous opportunity to revitalize its ailing body occurred. I heard sad stories about the administrative corruption and mismanagement of funds that plagued so many like institutions and having taught at a HBCU that had similar woes, I felt the pain of those bemoaners. My image of Bishop was colored by the constant barrage of newspaper articles that harped on and on about the bad financial health of the school and this image wasn’t helped by the recent experience I had when arriving and attending the National Conference of Artists annual meeting hosted by Bishop and the Museum of African American Life and Culture. My first impression of the campus was “Oh my God, what bomb was dropped on this place!” The fact that the college was ill-prepared to host this body of artists from around the African Diaspora was undeniable. Unfortunately, the college didn’t realize that by not having the necessary amenities to successfully host NCA, it made a lasting impression on the attendees that wasn’t complimentary. In fact, the disastrous meeting only served to solidify in my mind what a sad state of affairs this Bishop College was in. But as is true of any institutional decline, the Bishop story at its end was hardly the full Bishop story. No one looks at the Fall of the Roman Empire as the definition of Rome’s contribution to world culture. To discount the years of triumph simply because in the end it crashed and burned is to render history irrelevant. Well in the case of Bishop College, Dallas has rendered its history irrelevant. It has allowed the end to define the beginning. It has wiped the slate clean as far as what Bishop meant to our city and its Black population is concerned. When Bishop moved from Marshall, TX to Dallas in 1961, one of the Dallas Citizens Council leaders stated that Bishop was one of the most significant institutions to come to Dallas in a long time. Others lauded the city for attracting such a prestigious school to our community. Bishop was impressive enough to attract a $1.5 million Ford Foundation grant, one of the largest given to a HBCU back in the early 1970s. That Bishop’s president, Dr. Milton Curry, Jr. saw fit to use a good portion of that money to enrich both the cultural offerings on the campus while simultaneously developing outreach programs to the community speaks highly of his visionary ideas about the role of a college in a community. Dr. Curry knew that for most HBCUs, their role extended well beyond simply educating students. Their role, by necessity, had to include uplifting the African American communities within which they dwelt. Make no mistake about it, Dr. Milton Curry, Jr. was a visionary. He foresaw a college that not only provided exemplary education but that gave Dallas its first glimpse of nationally prominent African/African American/Caribbean cultural luminaries. Bishop introduced Dallas to the likes of Maya Angelou (long before she became “famous”), Alex Haley (pre-ROOTS fame), Eleo Pomare (banned in some cities for his revolutionary choreography!), Nikki Giovanni (young, fiery poet), Alvin Ailey (now well known in Dallas, but not then), Ruby Dee & Ossie Davis (theater & film artists and activists), Poet Laureate Gwendolyn Brooks, South African poet/activist Kgotsitsile, and so many more. Its Fine Arts Lyceum Series under the leadership of Rev. Rhett James brought notable lecturers to the city who enlivened the intellectual offerings of a segregated city and helped Black Dallas join the national discourse on topics such as race, social justice, and cultural equity. Bishop, thanks to the vision of Dr. Curry, spawned two of our most influential African American cultural institutions, Dallas Black Dance Theatre and the African American Museum, formerly the Museum of African American Life and Culture. So many of the musicians we all take for granted in the Dallas music scene, musicians like Roger Boykin, Norman Fisher, Dean Hill, Wendell Sneed, Linda Searight, Glenda Cole Clay, Joyce Lofton, to name a few, are the products of Bishop College. The late Dr. Thelma Thompson Daniels, former Dean of Humanities at Bishop,inspired many Bishopites and non-Bishopites to embrace African American literature. One of my most prized possessions is the anthology Dr. Daniels gave me of African American literature dating back to the first known publication of a Black writer. Bishop College; this little treasure on the hill, this institution of higher learning, this cultural fount deserves to be remembered for the things it did to invigorate the cultural development of Dallas, black and white, and the legacy of cultural excellence that is carried onward today by the many Bishop alumni both here in Dallas and across the nation. Good Ole Bishop Blue, a Black institution that made an indelible mark on Good Ole Big-D. Lest we forget…